Section 3: Software Development as a Process

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can we design and write ‘good’ software that meets its goals and requirements?

Objectives

Describe the differences between writing code and engineering software.

Define the fundamental stages in a software development process.

List the benefits of following a process of software development.

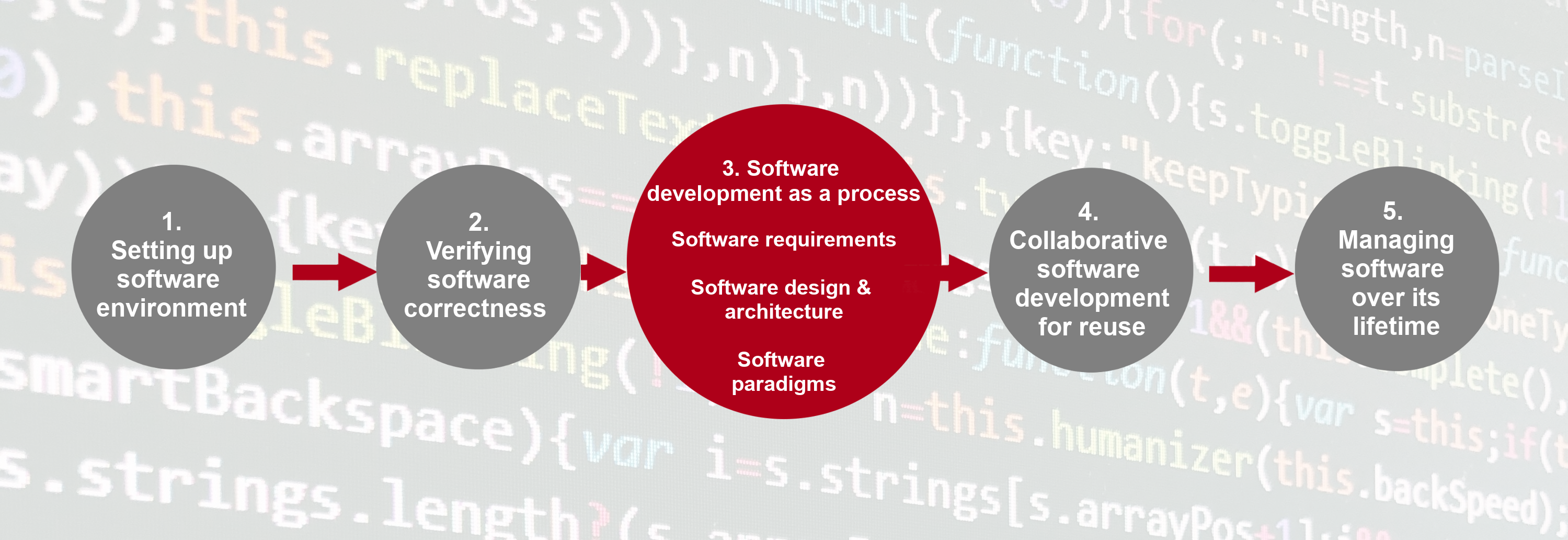

In this section, we will take a step back from coding development practices and tools and look at the bigger picture of software as a process of development.

“If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.” - Benjamin Franklin

Writing Code vs Engineering Software

Traditionally in academia, software - and the process of writing it - is often seen as a necessary but throwaway artefact in research. For example, there may be research questions (for a given research project), code is created to answer those questions, the code is run over some data and analysed, and finally a publication is written based on those results. These steps are often taken informally.

The terms programming (or even coding) and software engineering are often used interchangeably. They are not. Programmers or coders tend to focus on one part of the software development process: implementation, more than any other. In academic research, often they are writing software for themselves - they are their own stakeholders. And ideally, they are writing software from a design, that fulfils a research goal to publish research papers.

Someone who is engineering software, on the other hand takes a wider view:

- The lifecycle of software: from understanding what is needed, to writing the software and using/releasing it, to what happens afterwards.

- Who will (or may) be involved: software is written for stakeholders. This may only be the researcher initially, but there is an understanding that others may become involved later (even if that isn’t evident yet). A good rule of thumb is to always assume that code will be read and used by others later on, which includes yourself!

- Software (or code) is an asset: software inherently contains value - for example, in terms of what it can do, the lessons learned throughout its development, and as an implementation of a research approach (i.e. a particular research algorithm, process, or technical approach).

- As an asset, it could be reused: again, it may not be evident initially that the software will have use beyond its initial purpose or project, but there is an assumption that the software - or even just a part of it - could be reused in the future.

The Software Development Process

The typical stages of a software development process can be categorised as follows:

- Requirements gathering: the process of identifying and recording the exact requirements for a software project before it begins. This helps maintain a clear direction throughout development, and sets clear targets for what the software needs to do.

- Design: where the requirements are translated into an overall design for the software. It covers what will be the basic software ‘components’ and how they’ll fit together, as well as the tools and technologies that will be used, which will together address the requirements identified in the first stage.

- Implementation: the software is developed according to the design, implementing the solution that meets the requirements set out in the requirements gathering stage.

- Testing: the software is tested with the intent to discover and rectify any defects, and also to ensure that the software meets its defined requirements, i.e. does it actually do what it should do reliably?

- Deployment: where the software is deployed and used for its intended purpose.

- Maintenance: where updates are made to the software to ensure it remains fit for purpose, which typically involves fixing any further discovered issues and evolving it to meet new or changing requirements.

The process of following these stages, particularly when undertaken in this order, is referred to as the waterfall model of software development: each stage’s outputs flow into the next stage sequentially.

Whether projects or people that develop software are aware of them or not, these stages are followed implicitly or explicitly in every software project. What is required for a project (during requirements gathering) is always considered, for example, even if it isn’t explored sufficiently or well understood.

Following a process of development offers some major benefits:

- Stage gating: a quality gate at the end of each stage, where stakeholders review the stage’s outcomes to decide if that stage has completed successfully before proceeding to the next one (and even if the next stage is not warranted at all - for example, it may be discovered during requirements of design that development of the software isn’t practical or even required).

- Predictability: each stage is given attention in a logical sequence; the next stage should not begin until prior stages have completed. Returning to a prior stage is possible and may be needed, but may prove expensive, particularly if an implementation has already been attempted. However, at least this is an explicit and planned action.

- Transparency: essentially, each stage generates output(s) into subsequent stages, which presents opportunities for them to be published as part of an open development process.

- It saves time: a well-known result from empirical software engineering studies is that it becomes exponentially more expensive to fix mistakes in future stages. For example, if a mistake takes 1 hour to fix in requirements, it may take 5 times that during design, and perhaps as much as 20 times that to fix if discovered during testing.

In this section we will place the actual writing of software (implementation) within the context of the typical software development process:

- Explore the importance of software requirements, the different classes of requirements, and how we can interpret and capture them.

- How requirements inform and drive the design of software, the importance, role, and examples of software architecture, and the ways we can describe a software design.

- Implementation choices in terms of programming paradigms, looking at procedural, functional, and object oriented paradigms of development. Modern software will often contain instances of multiple paradigms, so it is worthwhile being familiar with them and knowing when to switch in order to make better code.

- How you can (and should) assess and update a software’s architecture when requirements change and complexity increases - is the architecture still fit for purpose, or are modifications and extensions becoming increasingly difficult to make?

Key Points

Software engineering takes a wider view of software development beyond programming (or coding).

Ensuring requirements are sufficiently captured is critical to the success of any project.

Following a process makes development predictable, can save time, and helps ensure each stage of development is given sufficient consideration before proceeding to the next.