Transferring files with remote computers

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How do I transfer files to (and from) the cluster?

Objectives

Transfer files to and from a computing cluster.

Performing work on a remote computer is not very useful if we cannot get files to or from the cluster. There are several options for transferring data between computing resources using CLI and GUI utilities, a few of which we will cover.

Download Files From the Internet

One of the most straightforward ways to download files is to use either curl

or wget. One of these is usually installed in most Linux shells, on Mac OS

terminal and in GitBash. Any file that can be downloaded in your web browser

through a direct link can be downloaded using curl -O or wget. This is a

quick way to download datasets or source code.

The syntax for these commands is: curl -O https://some/link/to/a/file

and wget https://some/link/to/a/file. Try it out by downloading

some material we’ll use later on, from a terminal on your local machine.

[user@laptop ~]$ curl -O https://nclrse-training.github.io/hpc-intro-cirrus/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

or

[user@laptop ~]$ wget https://nclrse-training.github.io/hpc-intro-cirrus/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

tar.gz?This is an archive file format, just like

.zip, commonly used and supported by default on Linux, which is the operating system the majority of HPC cluster machines run. You may also see the extension.tgz, which is exactly the same. We’ll talk more about “tarballs,” since “tar-dot-g-z” is a mouthful, later on.

Transferring Single Files and Folders With scp

To copy a single file to or from the cluster, we can use scp (“secure copy”).

The syntax can be a little complex for new users, but we’ll break it down.

The scp command is a relative of the ssh command we used to

access the system, and can use the same public-key authentication

mechanism.

To upload to another computer:

[user@laptop ~]$ scp path/to/local/file.txt yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:/path/on/Cirrus

To download from another computer:

[user@laptop ~]$ scp yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:/path/on/Cirrus/file.txt path/to/local/

Note that everything after the : is relative to our home directory on the

remote computer. We can leave it at that if we don’t care where the file goes.

[user@laptop ~]$ scp local-file.txt yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:

Upload a File

Copy the file you just downloaded from the Internet to your home directory on Cirrus.

Solution

[user@laptop ~]$ scp hpc-intro-data.tar.gz yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:~/

Most computer clusters are protected from the open internet by a firewall.

This means that the curl command will fail, as an address outside the

firewall is unreachable from the inside. To get around this, run the curl or

wget command from your local machine to download the file, then use the scp

command to upload it to the cluster.

Why Not Download on Cirrus Directly?

Try downloading the file directly. Note that it may well fail, and that’s OK!

Commands

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk [yourUsername@cirrus-login1 ~]$ curl -O https://nclrse-training.github.io/hpc-intro-cirrus/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gz or [yourUsername@cirrus-login1 ~]$ wget https://nclrse-training.github.io/hpc-intro-cirrus/files/hpc-intro-data.tar.gzDid it work? If not, what does the terminal output tell you about what happened?

To copy a whole directory, we add the -r flag, for “recursive”: copy the

item specified, and every item below it, and every item below those… until it

reaches the bottom of the directory tree rooted at the folder name you

provided.

[user@laptop ~]$ scp -r some-local-folder yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:target-directory/

Caution

For a large directory – either in size or number of files – copying with

-rcan take a long time to complete.

What’s in a /?

When using scp, you may have noticed that a : always follows the remote

computer name; sometimes a / follows that, and sometimes not, and sometimes

there’s a final /. On Linux computers, / is the root directory, the

location where the entire filesystem (and others attached to it) is anchored. A

path starting with a / is called absolute, since there can be nothing above

the root /. A path that does not start with / is called relative, since

it is not anchored to the root.

If you want to upload a file to a location inside your home directory –

which is often the case – then you don’t need a leading /. After the

:, start writing the sequence of folders that lead to the final storage

location for the file or, as mentioned above, provide nothing if your home

directory is the destination.

A trailing slash on the target directory is optional, and has no effect for

scp -r, but is important in other commands, like rsync.

A Note on

rsyncAs you gain experience with transferring files, you may find the

scpcommand limiting. The rsync utility provides advanced features for file transfer and is typically faster compared to bothscpandsftp(see below). It is especially useful for transferring large and/or many files and creating synced backup folders.The syntax is similar to

scp. To transfer to another computer with commonly used options:[user@laptop ~]$ rsync -avzP path/to/local/file.txt yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:directory/path/on/Cirrus/The options are:

a(archive) to preserve file timestamps and permissions among other thingsv(verbose) to get verbose output to help monitor the transferz(compression) to compress the file during transit to reduce size and transfer timeP(partial/progress) to preserve partially transferred files in case of an interruption and also displays the progress of the transfer.To recursively copy a directory, we can use the same options:

[user@laptop ~]$ rsync -avzP path/to/local/dir yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:directory/path/on/Cirrus/As written, this will place the local directory and its contents under the specified directory on the remote system. If the trailing slash is omitted on the destination, a new directory corresponding to the transferred directory (‘dir’ in the example) will not be created, and the contents of the source directory will be copied directly into the destination directory.

The

a(archive) option implies recursion.To download a file, we simply change the source and destination:

[user@laptop ~]$ rsync -avzP yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:path/on/Cirrus/file.txt path/to/local/

All file transfers using the above methods use SSH to encrypt data sent through

the network. So, if you can connect via SSH, you will be able to transfer

files. By default, SSH uses network port 22. If a custom SSH port is in use,

you will have to specify it using the appropriate flag, often -p, -P, or

--port. Check --help or the man page if you’re unsure.

Change the Rsync Port

Say we have to connect

rsyncthrough port 768 instead of 22. How would we modify this command?[user@laptop ~]$ rsync test.txt yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:Solution

[user@laptop ~]$ rsync --help | grep port --port=PORT specify double-colon alternate port number See http://rsync.samba.org/ for updates, bug reports, and answers [user@laptop ~]$ rsync --port=768 test.txt yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk:

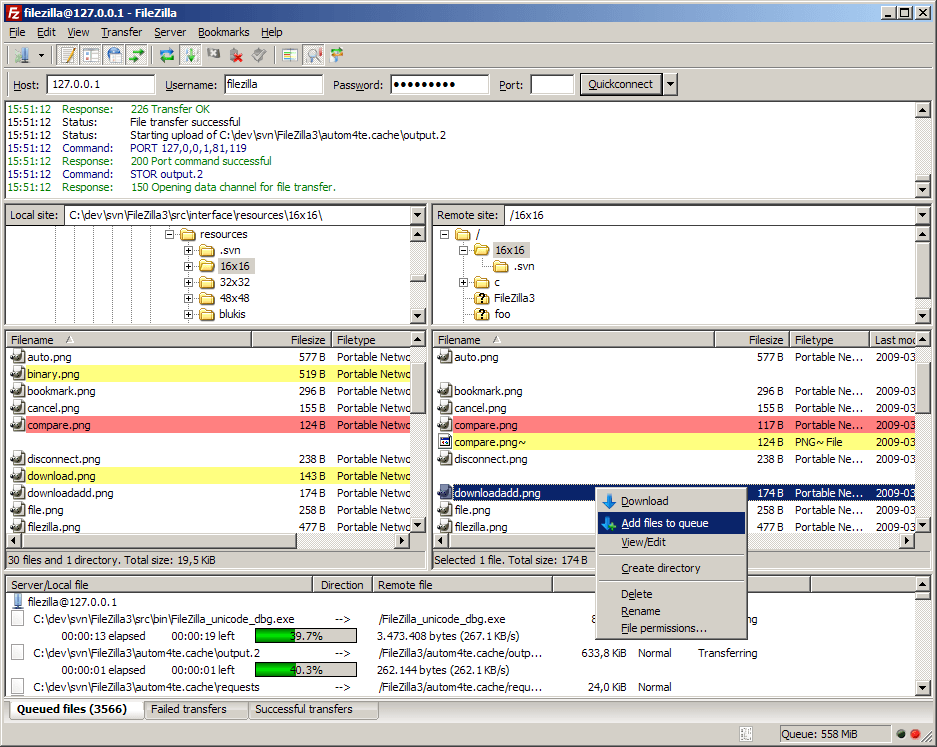

Transferring Files Interactively with FileZilla

FileZilla is a cross-platform client for downloading and uploading files to and

from a remote computer. It is absolutely fool-proof and always works quite

well. It uses the sftp protocol. You can read more about using the sftp

protocol in the command line in the

lesson discussion.

Download and install the FileZilla client from https://filezilla-project.org. After installing and opening the program, you should end up with a window with a file browser of your local system on the left hand side of the screen. When you connect to the cluster, your cluster files will appear on the right hand side.

To connect to the cluster, we’ll just need to enter our credentials at the top of the screen:

- Host:

sftp://login.cirrus.ac.uk - User: Your cluster username

- Password: Your cluster password

- Port: (leave blank to use the default port)

Hit “Quickconnect” to connect. You should see your remote files appear on the right hand side of the screen. You can drag-and-drop files between the left (local) and right (remote) sides of the screen to transfer files.

Finally, if you need to move large files (typically larger than a gigabyte)

from one remote computer to another remote computer, SSH in to the computer

hosting the files and use scp or rsync to transfer over to the other. This

will be more efficient than using FileZilla (or related applications) that

would copy from the source to your local machine, then to the destination

machine.

Archiving Files

One of the biggest challenges we often face when transferring data between remote HPC systems is that of large numbers of files. There is an overhead to transferring each individual file and when we are transferring large numbers of files these overheads combine to slow down our transfers to a large degree.

The solution to this problem is to archive multiple files into smaller numbers of larger files before we transfer the data to improve our transfer efficiency. Sometimes we will combine archiving with compression to reduce the amount of data we have to transfer and so speed up the transfer.

The most common archiving command you will use on a (Linux) HPC cluster is

tar. tar can be used to combine files into a single archive file and,

optionally, compress it.

Let’s start with the file we downloaded from the lesson site,

hpc-into-data.tar.gz. The “gz” part stands for gzip, which is a

compression library. Reading this file name, it appears somebody took a folder

named “hpc-intro-data,” wrapped up all its contents in a single file with

tar, then compressed that archive with gzip to save space. Let’s check

using tar with the -t flag, which prints the “table of contents”

without unpacking the file, specified by -f <filename>, on the remote

computer. Note that you can concatenate the two flags, instead of writing

-t -f separately.

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@login.cirrus.ac.uk

[yourUsername@cirrus-login1 ~]$ tar -tf hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

hpc-intro-data/

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01971Z.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goostats

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goodiff

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02018B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01736A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01812A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843B.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729A.txt

hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040Z.txt

This shows a folder containing another folder, which contains a bunch of files.

If you’ve taken The Carpentries’ Shell lesson recently, these might look

familiar. Let’s see about that compression, using du for “disk

usage”.

[yourUsername@cirrus-login1 ~]$ du -sh hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

36K hpc-intro-data.tar.gz

Files Occupy at Least One “Block”

If the filesystem block size is larger than 36 KB, you’ll see a larger number: files cannot be smaller than one block.

Now let’s unpack the archive. We’ll run tar with a few common flags:

-xto extract the archive-vfor verbose output-zfor gzip compression-ffor the file to be unpacked

When it’s done, check the directory size with du and compare.

Extract the Archive

Using the four flags above, unpack the lesson data using

tar. Then, check the size of the whole unpacked directory usingdu.Hint:

tarlets you concatenate flags.Commands

[yourUsername@cirrus-login1 ~]$ tar -xvzf hpc-intro-data.tar.gzhpc-intro-data/ hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/ hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01971Z.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goostats hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/goodiff hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02018B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01978A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01736A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01812A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02043A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01843B.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01751A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE01729A.txt hpc-intro-data/north-pacific-gyre/NENE02040Z.txtNote that we did not type out

-x -v -z -f, thanks to the flag concatenation, though the command works identically either way.[yourUsername@cirrus-login1 ~]$ du -sh hpc-intro-data 77K hpc-intro-dataWas the Data Compressed?

Text files compress nicely: the “tarball” is one-quarter the total size of the raw data!

If you want to reverse the process – compressing raw data instead of

extracting it – set a c flag instead of x, set the archive filename,

then provide a directory to compress:

[user@laptop ~]$ tar -cvzf compressed_data.tar.gz hpc-intro-data

Working with Windows

When you transfer text files to from a Windows system to a Unix system (Mac, Linux, BSD, Solaris, etc.) this can cause problems. Windows encodes its files slightly different than Unix, and adds an extra character to every line.

On a Unix system, every line in a file ends with a

\n(newline). On Windows, every line in a file ends with a\r\n(carriage return + newline). This causes problems sometimes.Though most modern programming languages and software handles this correctly, in some rare instances, you may run into an issue. The solution is to convert a file from Windows to Unix encoding with the

dos2unixcommand.You can identify if a file has Windows line endings with

cat -A filename. A file with Windows line endings will have^M$at the end of every line. A file with Unix line endings will have$at the end of a line.To convert the file, just run

dos2unix filename. (Conversely, to convert back to Windows format, you can rununix2dos filename.)

Data Limits and File Systems

Note that file systems and storage quotas will differ between HPC platforms.

On Cirrus, every project has an allocation on the work file system and your project’s space can always be accessed via the path

/work/[project-code]. The work file system is approximately 400 TB in size and is implemented using the Lustre parallel file system technology. There are currently no backups of any data on the work file system. Ideally, the work file system should only contain data that is actively in use, recently generated and in the process of being saved elsewhere or being made ready for up-coming work. This file system is visible from the login and compute nodes.Make sure that important data is always backed up elsewhere and that your work would not be significantly impacted if the data on the work file system was lost.

Every project has an allocation on the home file system and your project’s space can always be accessed via the path

/home/[project-code]. The home file system is approximately 1.5 PB in size and is implemented using the Ceph technology. This means that this storage is not particularly high performance but are well suited to standard operations like compilation and file editing. This file system is visible from the Cirrus login nodes but not compute nodes.There are currently no backups of any data on the home file system.

More information on using the solid state storage on Cirrus can be found in the Solid state storage section of the user guide.

Key Points

wgetandcurl -Odownload a file from the internet.

scpandrsynctransfer files to and from your computer.You can use an SFTP client like FileZilla to transfer files through a GUI.